Software projects often come with a README file. Important bits of documentation live here: set-up information, configuration options, known bugs, etc. A well-written README can make it easier to use a new program.

Michael Lopp (VP Eng @ Slack) gets credit for popularizing the concept of a personal README – in his words: “a user guide for me and how I work.” The concept resonated widely and personal READMEs are becoming more common (and appropriately critiqued).

I decided to write one. It proved a valuable exercise, and I’ve since shared it with my team. I figured I’d post it here, too – perhaps you’ll find it helpful! (Or at least amusing 😉…)

Charley’s README

Hey there! This is my personal README. It’s meant to:

- Help you get the most from our working relationship

- Proactively identify patterns in my behavior

- Make things explicit that were previously intuited or inferred

It is, in no way, meant to:

- Replace substantive conversations or trust-building

- Excuse my mistakes or unproductive behaviors

- Force you into operating “on my terms”

For new folks I’m going to work with closely, we’ll likely discuss this document explicitly as we ramp up together. For folks I’ve worked with for some time, I hope everything here rings true.

How I communicate

I think it can be hard to convey nuance/intent in short-form writing (e.g. Slack, code reviews, emails). As such, I do my best to explicitly indicate urgency+expectations. For example, I’ll often start a conversation with:

- “Whenever you have a second, could you …”

- “Just FYI: …”

- Occasionally: “Hey, urgent question: …”

For me, these qualifiers help make text-based communication less stressful. I’d ask that you loosely follow this pattern when pinging me – notably, if you have something that is time-sensitive, please say so upfront.

Other notes on my written communication:

- I use the “:thumbsup:” (👍) emoji to mean “makes sense”, “got it”, and “sounds good”. I use it a lot.

- In longer conversations, I’ll often type out “Mmmm” (or “mmm”) mid-conversation or as you’re typing. This is me “nodding my head” and indicating “I’m following along, keep going”.

- I often respond to asks/requests with “kk” or “roger” or something equally short. This can come off as brusque or disagreeable, but that’s not my intention. (If I disagree with an ask or don’t want to do something, I’ll articulate my concerns. I strive to not be passive-aggressive.)

How you work

I believe that developing strong time-management skills is key to a fulfilling + sustainable + productive engineering career. To me, this means knowing when and where you work best, and how to best integrate work with the rest of your life. Some people have this all figured out; others are still experimenting. (And it’s no fixed thing – life changes over time!) As such, the details of your work routine is up to you: starting early/staying late/weekends/etc (as is appropriate per our company’s expectations and office culture). I think creating healthy work/life boundaries are crucial, but I also believe that they look different for everyone. If you’re feeling self-conscious about hours or location, or would like to request specific accommodations, let’s talk about it live.

Responsiveness

I often work early (MT timezone) and send messages out before others are working – I don’t expect you to be online or respond to these! (I just can’t keep them all queued up in my head.) Similarly, if you send me messages at night, I’m likely not going to respond quickly. I rely on you to set your devices’ notifications settings appropriately to respect your own boundaries.

There are methods of escalation (e.g. OpsGenie) for emergencies.

How I give feedback

I aim to make 90% of my feedback positive. Following meetings or Slack interactions, this often looks something like:

- “I thought you responded to [Person X]’s questions well. It felt like you came well-prepared.”

- “Thanks for being proactive in surfacing [Concern X]”

- “I appreciate you jumping in at the end there – I forgot you had worked on [Project X]”

And in code reviews, it might be:

- “Nice job handling this edge case, great attention to detail”

- “I like how you’ve split this into manageable chunks – makes it way more readable”

- “This comment is super helpful! Makes understanding this block 1000% easier”

When you get such a comment from me, don’t feel obliged to reply or elaborate. In general, I try to give feedback promptly, so expect such commentary to arrive early and often (and typically via Slack).

I have a framework for giving constructive/“negative” feedback, but it’s out of scope for this document. If you’re my manager or report, I expect we’ll discuss it live at some point.

1:1s

I like to have weekly, 30-minute 1:1s with my manager and reports. The nature of these 1:1s will vary over time, but here’s my general approach.

With my manager: I’ll usually come prepared with things I want to discuss. I like to write down action items as we’re talking. A common topic is “troubleshooting”, things like:

- “[Meeting X] seemed to go poorly, and I’m not sure why.”

- “[Person X] and I aren’t gelling on this project, can we discuss?”

- “Does it seem like [Project X] is dragging on?”

The goal for these topics is to get your perspective and see how I can adapt or you can assist.

With my reports: 1:1s are a time to discuss what’s on your mind. Ideally, over time, we’ll surface ways I can help improve your day-to-day. Good starting points are often things like:

- “I feel like [Project X] is going poorly/well/just OK.”

- “I’m getting sick of writing Javascript components all day. Can we make a change?”

- “[Person X] sits next to me and all their phone calls are driving me nuts.”

I’ll also use the time to rely any important top-down info I’ve got. Expect me to jot down TODOs as we talk – it’s the only way I can remember things. Some 1:1s will flow with good conversation, and some will be awkward and fluffy – that’s just how these things work.

I think those are the biggies. Please let me know if you’ve got any feedback on it – I hope it evolves over time. Thank you for reading and I look forward to working together!

Charley

The above is a snapshot of my README from August 2019. The living document is available on Google Docs.

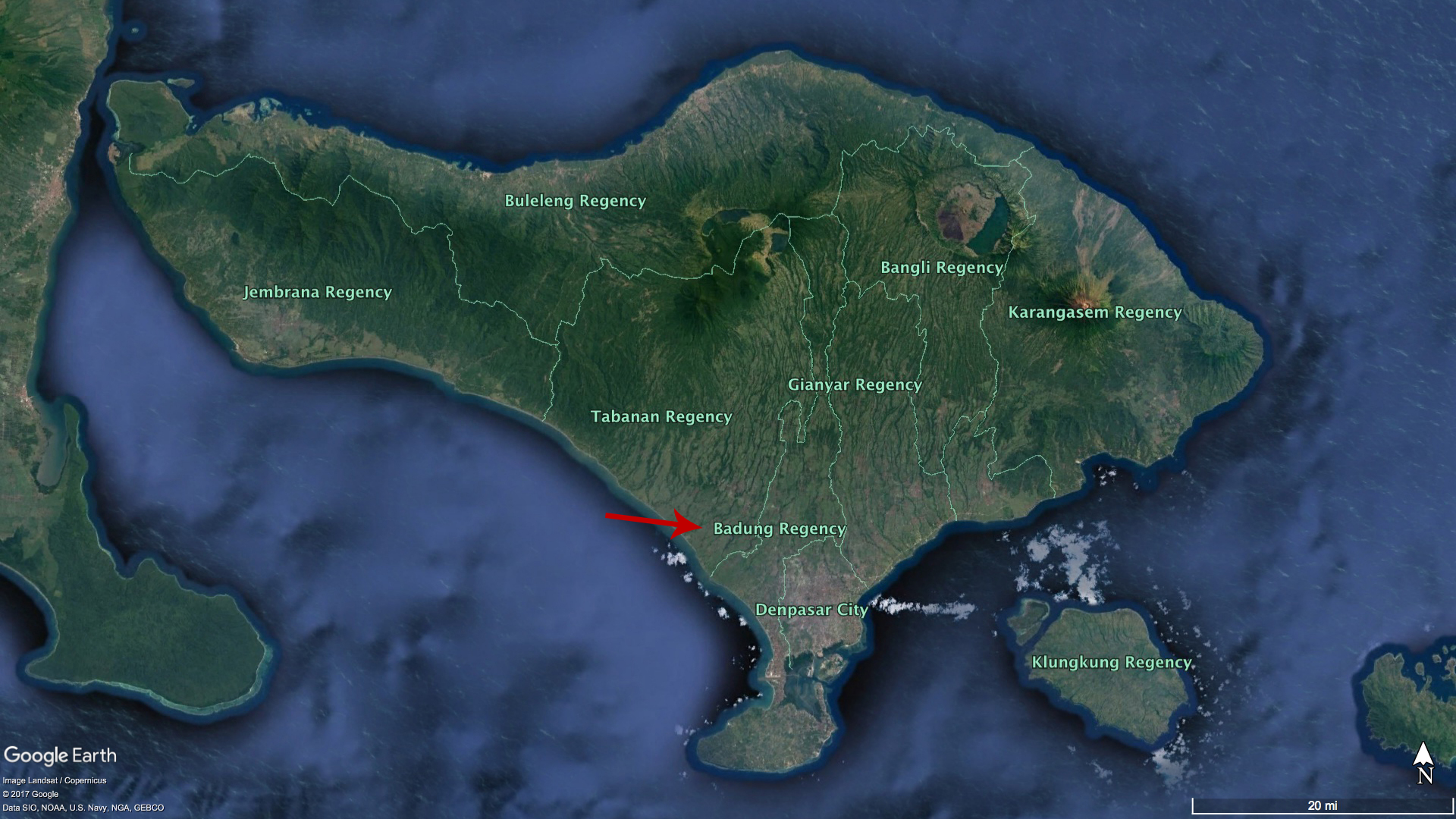

Here’s an animation showing all six of Badung’s districts in succession:

Here’s an animation showing all six of Badung’s districts in succession: